Baku: A Walk Through Azerbaijan’s Ultra-Modern Metropolis

/Hypermodern and distinctly sanitised, I found Baku a tricky city to warm to. But walking through Azerbaijan’s gleaming capital is an eye-opening experience

Baku | Bakı | Pop. 2.26 million

Baku was the last of the Caucasus capitals that I visited. It also turned out to be my least favourite. Compared with the flamboyance of Tbilisi and the friendliness of Yerevan, Baku was a wily kind of place.

That’s not to say I didn’t enjoy my time there. Azerbaijan’s clean, wealthy, weirdly subdued capital is a genuinely fascinating place to spend a few days. (It’s also a good base if you’re planning to take daytrips to nearby tourist destinations like Qobustan.)

As I walked through Baku, taking photos, I noticed that it was almost impossible to point a camera at anything without the result looking like a wry piece of social commentary on the strange mix of old and new. Mosques share street space with designer boutiques. Soviet-era Ladas drive alongside Porsches on the roads. Over medieval alleyways, the Flame Towers loomed.

Baku is a city that has visibly felt the flush of serious financial investment - hence the nickname, ‘Dubai on the Caspian’. Indeed, much like the UAE, Azerbaijan knows its oil won’t last forever, which is why so much money has been invested in Baku’s touristic infrastructure - to mixed results.

The Bulvar

I stayed at an Airbnb property on Neftchilar Avenue, a thundering six-lane highway that runs alongside the Bulvar: the waterfront boulevard in the middle of the city.

Traffic throughout the Caucasus is batshit crazy, and here in Baku it reaches its absolute zenith. You walk around the city to a soundtrack of car horns and policemen’s whistles. Traffic jams at crossroads sends vehicles grinding in Brownian motion through each other. Luckily for pedestrians, there are underpasses everywhere: empty, slightly eerie places, only brought to life by the odd busker.

En route to the Old Town, I walked past designer stores and Starbucks-style coffee shops. One morning, I ate breakfast at Cookshop, and struck up a conversation with a staff member in there, a young guy who had moved to Baku to study. As soon as I mentioned that I’d visited Armenia, things became awkward.

‘Bad country,’ he told me. ‘They have twenty percent of our land.’ He was referring to Nagorno-Karabakh, the disputed territory occupied by Armenian forces. You’ll hear similarly negative opinions about Azerbaijan in Armenia - since the conflict in the early Nineties, tensions between the two countries haven’t thawed a bit.

Içeri Sehar: Baku’s Old Town

MAIDEN’S TOWER IN BAKU’S OLD TOWN

Baku’s touristic centre of gravity is Içeri Sehar, or the Old Town. Attractions here include Qız Qalası (Maiden’s Tower), one of the oldest buildings in Baku and one whose origins are shrouded in mystery. There’s also the Palace of the Shirvinshahs, a fifteenth-century complex that takes you back to the days of the ruling Shirvin dynasty.

A landscape of narrow streets, domed roofs and minarets, Baku’s Old Town is utterly Middle Eastern in flavour. These are the sort of streets that I expected to be thrumming with mercantile life: chatter, haggling, carts being pulled back and forth. There were stores selling trinkets, embroidered bags, traditional sheepskin hats and carpets. But beyond these tourist shops, all I found were cats, and the odd clothesline. The Old Town felt strangely evacuated.

My first impressions of the Old Town were also soured by a bad experience at a restaurant. Rather than show me a menu, the waiter suggested I try a selection of qutab (stuffed Azeri flatbreads) - and brought me enough for two people. When I managed to get my hands on a menu, I found two different sets of prices inside: presumably one for locals, one for tourists. It came as no surprise when a hugely over-inflated bill came along, and although I got a few manat knocked off, I left in a bad mood, and permanently suspicious everywhere I ate in Baku thereafter.

That said, the absence of crowds makes the Old Town a perfect place for a leisurely, rather than frantic, walk. There are plenty of beautiful, shaded little park areas, and cafes to enjoy a glass of tea. I also enjoyed watching the shopkeepers play games of nərd (backgammon) outside their stores.

The Waterfront

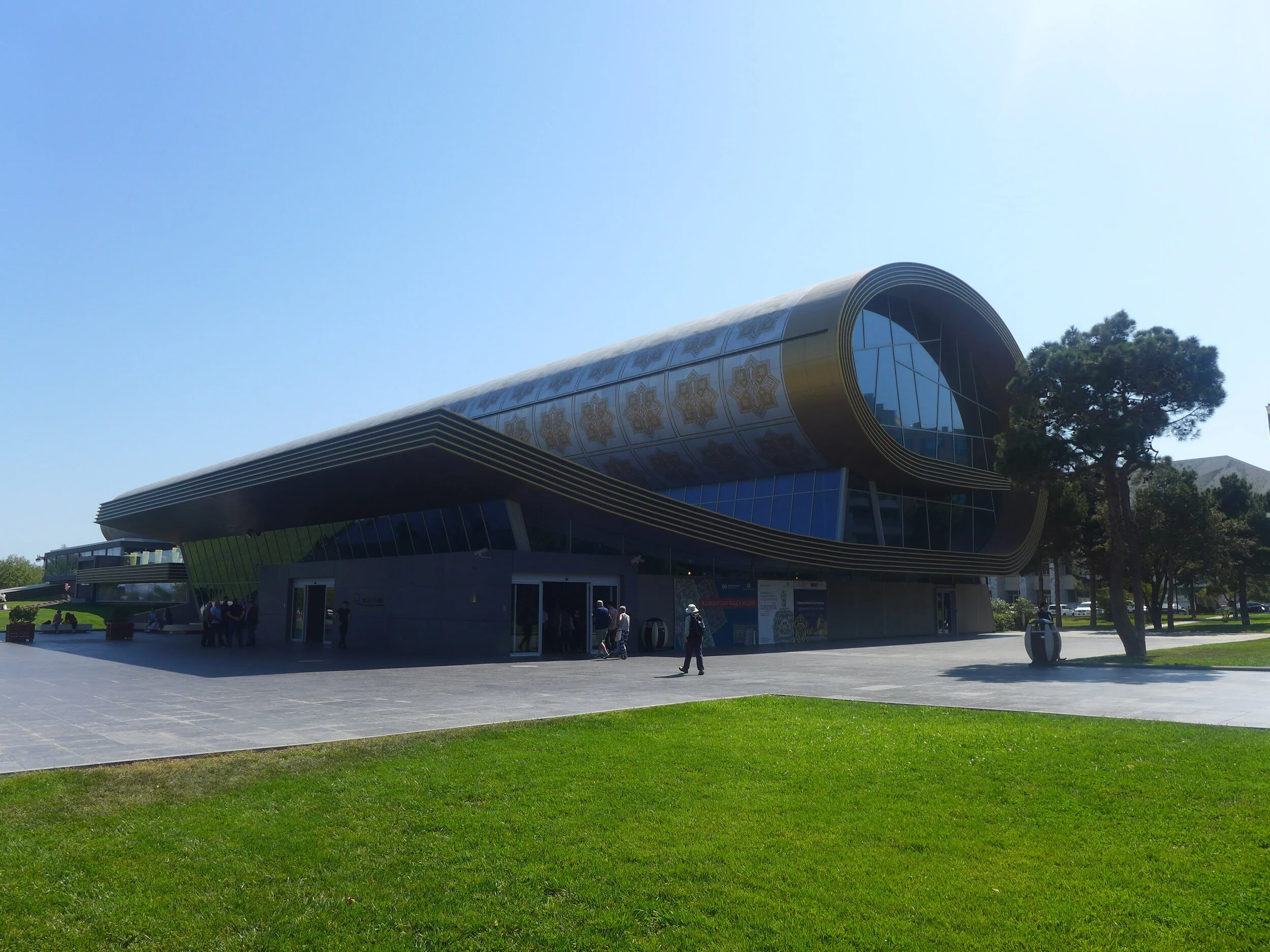

From the Old Town I walked down to the waterfront, and to the westernmost end of the Bulvar, where it met the yachting marina. Clean and inoffensive, it reminded me a little of quayside Sydney, with a touch of hyperreality thrown in for good measure. There’s Little Venice, an absurdly naff restaurant/waterway complex where people are ferried along not on gondolas but motorboats, and the Azerbaijan Carpet Museum (pictured below, if you hadn’t already guessed).

Further on, I got to the Caspian Waterfront Mall, a retail destination that feels a bit out of place by the harbour, and the Baku Crystal Hall, a building that I remember seeing on Eurovision when Azerbaijan hosted in 2012. Baku is covered in these big, expensive, self-aggrandising buildings. The city made a bid for both the 2016 and 2020 Summer Olympics - and while it failed on both occasions, it’s surely only a matter of time before the capital has its moment in the limelight on the world stage. (Not that Eurovision isn’t an event of great international prestige, obviously.)

The Funicular to the Flame Towers

From the waterfront, I found myself at the Baku Funicular, which takes passengers up to Martyr’s Lane, a plateau of land that offers you views across the Absheron Peninsula. The Funicular wasn’t due for another 30 minutes, so I decided to take the steps that ran parallel. Halfway up, I stopped beside the gates to the Yaşıl Teatr (Green Theatre), and jumped when I saw a guard, holding an automatic rifle, sat in the shadows. He made it clear that photography wasn’t permitted here, and that I’d better move along.

This whiff of authoritarianism is pretty common across Baku: you’ll often find surly-looking police or army officers stationed at seemingly random points around the city centre. I’ve heard stories of some policemen asking tourists for their passports and visa papers, basically giving them empty threats in the hope for an easy bribe, but I didn’t encounter this.

The views from Martyr’s Lane out across the Absheron Peninsula are spectacular. Looking out across the Caspian, I suddenly felt I was at the edge of another part of the world, and I was. On the other side of the sea lay Turkmenistan, and the rest of Central Asia. I asked a middle-aged man to take a photo of me in front of the nearby Flame Towers. It was an incredibly bad photo, but the man invited me to his home in Iran and was so nice I didn’t have the heart to tell him take another.

There no other buildings in Baku that quite symbolise Azerbaijan’s leap forward into modernity than the Flame Towers. (Azerbaijan, incidentally, translates as ‘land of fire’, which comes from its roots as a nation of Zoroastrian fire-worshippers.) This trio of skyscrapers contains homes, offices, restaurants, a hotel and a Lamborghini dealership among other things. At night, they light up and project fire-like displays or the Azerbaijani flag across their glass surfaces.

Eating and drinking in Baku

Although Azerbaijan is a Muslim country, attitudes to drinking seem relaxed in Baku. (Read: it was the first place in the Caucasus where I saw a shitfaced local get carried out of a bar by his mates.) It took a while for me to find anything you might call a drinking scene here.

On my first night in town, I went out drinking with Dom and Ben, a couple of English guys I first met in Yerevan. All we found in the streets around Fəvvarələr Meydanı was a rash of English and Irish-style pubs with names like the William Shakespeare and Finnegans, where middle-aged Western expats propped up the bar alongside Azeri sex workers. Not exactly buzzing hotspots.

That, admittedly, was a Monday night. Later in the week, I found more life in the bars north of Fəvvarələr Meydanı, where locals outnumbered the foreigners. I enjoyed the live acoustic Azeri music I saw at Old Room Bar. On a Friday night, I visited Kefli, a chic wine bar filled with trendy, black-wearing Bakuvians (pictured above), and Barrel Playground, an alfresco bar that reminded me a little of Boxpark Shoreditch in London.

SHIRVINSHAH MUSEUM RESTAURANT

When it comes to places to eat, I was disappointed to find that most of the restaurants around the Old Town are burger, pizza and other Western-style places that seem to operate under the philosophy that tourists never want to try anything outside their own cuisine. I asked Murad, my Airbnb host, to recommend any traditional restaurants popular with Bakuvians. He warned me that most places would try and take advantage of me - but he did suggest the Shirvanshah Museum Restaurant. This is an odd place, a kind of restaurant that doubles as a museum where each dining spaces is modelled around a different period in Azerbaijani history. But the food was delicious, and I was happy to try Azeri cuisine: kebabs, dolma and - my favourite - plov (rice flavoured with currants and apricots).

One of my fondest memories of Baku was a surreal morning when I walked into a grubby little cafe, well off the beaten track, on my way to Taza Bazaar. The elderly lady in there didn’t speak any English, but she put together a lovely breakfast of scrambled eggs and tomatoes for me. Two gentlemen also sat in there stared at me for a insisted that couple of minutes, then invited me to drink vodka with them. It’s not something I normally drink at 10am, though I’ll admit it seemed to help my haggling skills in the bazaar.

A VENDOR AT BAKU’S TAZA BAZAAR

The cafe owner and those two men were kind, warm-hearted people, and I don’t doubt that the Azeri spirit is just as generous, hospitable and eccentric as that of neighbouring Georgia and Armenia. I just can’t help but feel that it’s been scrubbed clean from the middle of Baku.

It was actually Eurovision that drew global attention, if briefly, to the city’s growing pains. The Azerbaijani government does not have a great human rights record, and it has been dogged by controversy surrounding the forced evictions of many of Baku’s residents, whose homes and businesses were bulldozed to make way for the Crystal Hall and all the rest of that box-fresh waterfront architecture. It made me more forgiving each time I scoured my bill at a restaurant, or counted my change at a bar, or refused to tip cab drivers. Entire neighbourhoods have been displaced in the name of tourism in Baku; is it any wonder that Bakuvians might treat foreigners like me as fair game?

Visitors with a taste for luxury, shopping and skyline selfies will love Baku. I’m more of a dirt-under-the-fingernails kind of person. If I go back to Azerbaijan (and I hope to), it will be to see the rest of the country, and how it compares to its slick, shrewd capital. MB